Tom Waits For No One

Tom Waits was on the classic send-up talk show "Fernwood 2 Night" with Martin Mull in 1977. I wasn't quite sure what to make of it. After he played "My Piano has been Drinking", Martin Mull said "It's kind of strange to have a guy sitting here with a bottle in front of him." Chewing on his words, with eyes half closed, Waits scratched his nose and replied, "I'd rather have a bottle in front of me than a frontal lobotomy." I was an immediate fan.

Ticket for the early show for Tom Waits at the Roxy Theater, 1977.

Later that spring, driving up from Laguna Beach to see Close Encounters of the Third Kind at the Cinerama Dome in Hollywood, we passed by Tom Waits' name on the marquee at The Roxy. The Dome had a line that wrapped three times around it, so we changed plans and headed for The Roxy to see what turned out to be a close encounter of different kind. Leon Redbone opened the intimate venue, and Waits' poetry-jazz performance art was evocative and mind blowing. The most memorable act of the evening was "Romeo is Bleeding". Growling out an LA tale with a lonely sax blaring, Waits wrapped himself around an inebriated lamp post, spinning a Gene Kelly umbrella beneath sparkling rain confetti. Wow. It was then that I realized his character was for real.

At the time, I was co-partnered in Lyon Lamb Video Animation Systems (VAS). The VAS was an innovative product and a game-changer for the animation industry. A request came in from film maker Ralph Bakshi to build something that didn't exist for his yet-to-be produced animated feature American Pop: "If you Lyon Lamb guys can build me a video rotoscope, I'll buy 10". So we built one.

We were ready to demo. With one phone call, we learned that Ralph had just spent $250,000 on 35mm equipment to go another direction. Out of curiosity, he came for the demo anyway. Ralph walked in and said "Where is it?!" He took one look at the demo and screeched in his Brooklyn accent "It fuckin' works!!!" and stomped out of the studio. The good news was, we had a new product. To prove its viability, we decided to make an animated short that would showcase the video rotoscope to the industry.

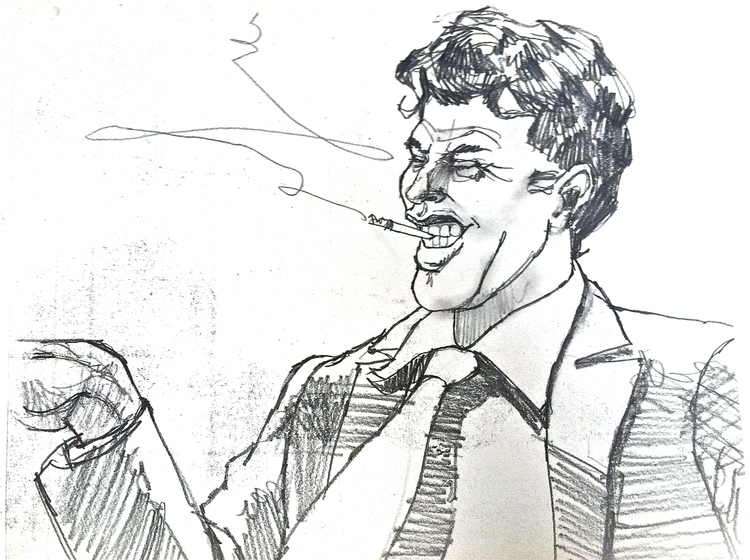

It was nearly two years before MTV's debut, and six years before an animated rock video would appear on MTV, but we were inspired by a burgeoning market: rock n' roll videos. All we needed was a subject... and then I recalled Waits at The Roxy. With his signature vocals and body language, Tom Waits' motion would translate beautifully into animation. Creative juices began flowing, a pitch was hatched, phone calls were returned, storyboards drawn, and after several meetings with Tom, sets were built and production began.

At the video shoot. Tom drove up in his '66 Blue Valentine T-bird and stepped out wearing a pork pie Stetson, an old wrinkled suit and carrying a bag, asking where the dressing rooms were. We're thinking "Whew, he's going to change that suit!" Then he came out of the dressing room with the same hat and a different old wrinkled suit.

For the shoot, we utilized 5 video cameras, 2 high, 2 low and 1 handheld. We did 6 takes with 2 separate dancers. We edited down 13 hours of video into to a 5 1/2 minute film, which was then traced frame by frame and turned into "Tom Waits For No One". Too early for MTV, the film premiered in 1979, lived one night with "Mike 'n Spike's Festival of Animation" and took first prize at a single Los Angeles film and video festival. Ralph Bakshi's rotoscoped American Pop was released in February 1981. On August 1, 1981, MTV went live and changed the world of music and video forever. Our little production, predating both, disappeared into obscurity.

After 35 years, in a world where music, video, animation, digital technology and young talent create new product on a global scale by the hour, "Tom Waits For No One" reaches out from the 20th century with the seeming draw of a throwback to analog itself. The live action images were hand traced frame by frame, turned into a caricatured drawing, inked onto a cel, then hand painted, photographed and edited on the most technology-forward analog video tools, by young artists who would transition into the 21st century's digital world to become leaders in their industries.

The production contents of Tom Waits For No One" and especially the scrapbook, have been close to my heart for decades. Through many ups, downs and mortality bending backflips, I've managed to hang onto most of the production elements from this film, which include the final cels, the drawings, the live action footage, the rotoscope itself and the video pencil tests created by this talented group of artists. Today, some of these elements are available to the public here, now.

In some ways, Tom Waits For No One has finally found a home, because of the digital age.

John Lamb